|

I'll

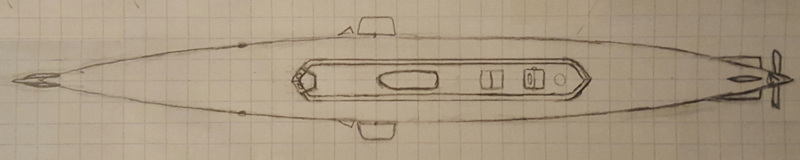

outline here some of my preferences and conclusions for design of the Nautilus. My focus is the exterior, though the layout

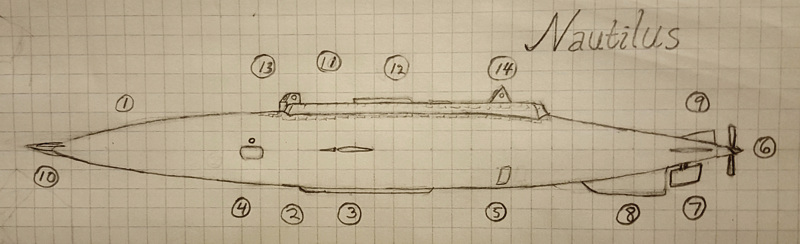

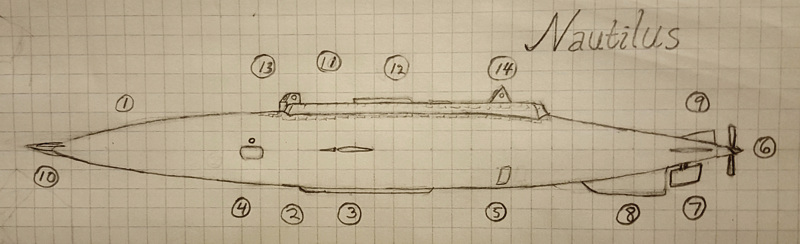

of course has to influence some design decisions. Figure 1 is a side

elevation; the numbers correspond to the design tour below.

I propose a traditional spindle, with raised platform,

pilothouse and light-house, a four-blade propeller with a free-turning

rudder forward of it, a lower fin, and some short stabilizers at the

tapered end. Some these features are based on period designs such as

the Hunley, and the conclusions of others in the catalog whose designs

reflect rewarding thought as well.

Two

big determinations will be discussed in due course: the manner of operation

of the pilothouse or wheelhouse, and of the illuminating lantern. I've followed the implications of the original illustrations,

with some interpretations or "clarifications" of my own intended

to best reflect "what Aronnax saw" even if the descriptions that

have come to us are incomplete. I provide a vertically retractable

wheelhouse at the front of the raised platform, and a triangular-profile

lantern aft that retracts like a 1970s car headlight.

To

commence the tour of this Nautilus design:

- The hull: I opt

for a spindle shape, with the 70mx8m dimensions

outlined by Nemo. The hull is capped by a flat platform, has a

ramming spur or prong at the bow just above the centerline, and a keel

slightly descended at the bottom. The plates are mostly smooth,

but overlap about 2cm where the hull meets the top platform, and the

siding of the platform (its top is smooth and flat).

- The

keel, whose weight and dimensions are given by Nemo, would be about

15-16 meters along the bottom of the boat. I have the keel extend about a quarter meter

from the bottom of the hull. It seems to

run slightly forward of the center of the spindle, as I assume (though I

am no maritime engineer) the mass of the keel (and the ram) need to

counterbalance the mass of the engine room aft.

- Two

movable diving planes are attached along the centerline on each

side of the hull, measuring about 3mx2m and positioned just slightly

forward of amidships. In front of these movable planes are two

small canards or winglets, to protect the planes from fouling and shock

on impact.

- The

Salon window: I place the Salon forward of the pilothouse, and follow

most of the designs on the Nautilus page. The window is an oblong

with rounded corners. Above the window is another floodlight

(unnoticed by Aronnax, who assumed the light came from the lighthouse).

- The

diving hatch door is positioned approximately below the lighthouse, as a

beacon to returning explorers. Probably the opposite side of

the diving chamber is a larger door to haul in the richest the

seas.

- The

propeller has four blades and a sturdy point on the hub, which extends

about a meter past the propeller, as we are told the Nautilus reversed

at speed to break out of the ice from this end. I ultimately did

not provide a ring or other enclosing protection around the screw,

though there is merit to the debate and the example of the Goff Nautilus

and the Hunley. I concluded however that any protective structure

would have to be so massive (as in some designs) as to completely

obscure the propeller, but that is not what Aronnax saw. Slighter

protection would merely become smashed and tangled in the Nautilus'

attack. Possibly the best studied example of the type of attacks the Nautilus

made - steel ramming a wooden ship - is ironically the ramming of PT-109

by the IJN Amagiri in 1943, in waters the Nautilus passed by en

route to Vanikoro. Kennedy's wooden PT-109 was sliced in two by

the Amagiri and sank in two sections (forward floating for several

days). The Amagiri however was damaged even in this unequal

contest: its starboard rudder was bent and affected the running of the

ship. This example, plus the three attacks recounted in 20kL (grazing

the Lincoln, the mysterious attack during Aegri Somnia, and the

Hecatomb attack), show the Nautilus too suffered damage at

least a third of the time. It was a hazardous means of attack. In

any case, I have mostly left the propeller free, and assume the

Nautilus carries a few spare blades!

- The

rudder, following Gagneux, is a freely turning, center-post rudder

forward of the propeller.

- Bottom

stabilizer: this fin is provided as a result of several

conclusions. It provides some anti-fouling protection to the rudder and

propeller. Also by being as deep as the keel of the Nautilus,

it can serve as a resting-fin for the numerous occasions the Nautilus

is described as resting on the ocean floor. Various measuring

devices could be attached to this as well as other designs have

provided.

- Vertical

stabilizer: while not so high as to noticeably break the surface, the vertical stabilizer steadies

the Nautilus and provides some protection to the propeller. As

other designs have found, this is a useful addition and Nemo might

have added it after the first sea trials himself!

- The

ram is one of themes important obscure features of the boat.

Usually described as a spur, never as a spear, but once as a

lightning-rod in the storms of the Atlantic, I ultimately added a prong

of about 3m, with reinforces flanges in a capital "Y" shape.

After considering a variety of knife-edge and chisel-tip

designs, such as used by the Confederate ironclad ram Virginia, I

concluded that the ram had to be a sturdy, somewhat vertically elongated

prong to punch open a ship's hull (or wretched cachalot or orca

body). We know it left a triangular impression in the Scotia,

hence the triangular pattern flanges. A long spear such as that of

the Plongeur would be too delicate. The ram could not be too

elaborate or extended to attach to the hull, given the separate

construction of various components.

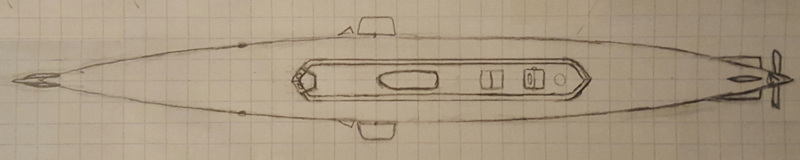

- The

platform is some 28 meters long, of parallel sides and pointed front and

back at a 108-degree angle, the angle of a regular pentagon. The sides

are angled at about 36-degree. The platform is about 3m wide (4m at

its base meeting the hull). The platform has retractable

poles for a rope balustrade along the sides. While the top

surface of the platform is flat, the iron plates along the edging of the

platform overlap slightly, as do the first ring of plates meeting the

platform on the hull.

- The

sealed longboat, sitting upright in its hull recess, rises

about half meter above the platform; aft of the boat is the main

hatch. There could be another hatch aft of the lighthouse.

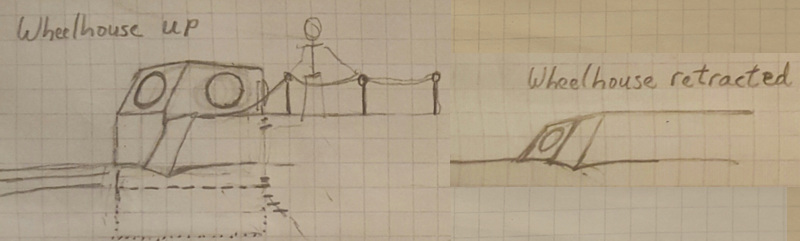

- The

pilothouse: Because of the practical demands for a functioning base of

navigation, the explicit need for the housing to retract into the hull

and still function, and the unclear descriptions and depictions of this

compartment, the wheelhouse presents altogether some of the most

vexed questions about the design of the Nautilus. Indeed

it may be that when a satisfactory explanation and depiction of the

wheelhouse is reached, the rest of the design flows into place around

it. My conclusions are intended to present the most practical

range of solutions. I opted for a regular pentagon, of

vertical sides, two meters high with the top meter normally rising above

the platform, with the two forward angled sides raked back 36

degrees for

the top meter of height. The cabin has portholes in all five

sides, but whenever the light is engaged, the rear window is

automatically closed (indeed the first action of engaging the light

would be to trigger the rear window closure so as not to blind the

occupants). I see this cover as a spring-loaded mechanism

sliding from bottom to top to cover the rear porthole. It is true

Aronnax, inside the pilothouse, saw four portholes. But

someone standing in front of one wall with a closed-off window behind,

and seeing four other walls around with portholes, may write

that they were in a four-sided chamber. The pilothouse is reached

from the back through a narrow hatch up a few steps. When

retracted the hatch is narrower still. When clearing the decks for

action, the pilothouse is pushed down to be flush with the platform.

The three back flat sides slide smoothly into the platform. The front of the wheelhouse becomes the front of the

platform, with the two forward windows forming the 36-degree raked angle

leading edge.

|

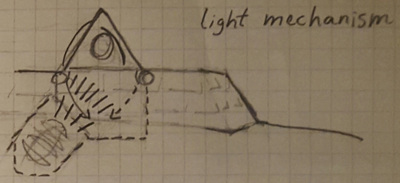

but forward of the housing

in the hull at about 30 degrees from vertical. The triangle contains additional movable lenses and mirrors to adjust the

direction of the light. The housing is

retractable, along both its forward and rear bases. Hinged at the

back, the large forward lens retracts safely into the

platform. When hinged at the front, the large lens points

straight up, to create a mysterious phosphorescent glow and to illuminate spaces

such as inside the coalmine volcano.

but forward of the housing

in the hull at about 30 degrees from vertical. The triangle contains additional movable lenses and mirrors to adjust the

direction of the light. The housing is

retractable, along both its forward and rear bases. Hinged at the

back, the large forward lens retracts safely into the

platform. When hinged at the front, the large lens points

straight up, to create a mysterious phosphorescent glow and to illuminate spaces

such as inside the coalmine volcano.